We noted earlier that even though the ruling People's Action Party has a supermajority which ensures the passage of any bill proposed by the cabinet, the key issues have always been whether the cabinet can gain the confidence of stakeholders and industry interests in the bill, whether there will be corrections or clarifications of the more unsettling portions of the bill, and whether the bill passed would satisfy that audience.

|

| Power is power, or is it? The power to pass laws is absolute power, or is it? |

So did the parliamentary debate provide suitable clarification to gain the confidence of industry interests and stakeholders?

(Note that appropriate links and quotes from Singapore's online "Hansard" or Parliamentary Report from the 7 and 8 May debate will be made available on this blog when they are published on the parliamentary website)

Two clarifications that were made

We at Illusio welcome two major clarifications made by the cabinet during the debate, which establish legislative intent of the bill.

We thank the law minister K Shanmugam for stating in parliament that the bill will not be used against statements of opinion, commentary, analysis, parody, satire, etc. He also reiterated his belief that a statement of fact is something that is clear-cut: it is or it isn't, and that a false statement of fact is equally clear-cut.

Whatever misgivings Singapore's civil rights activists have against Mr Shanmugam or the intention behind the bill, any challenge in court will rest exactly on what the minister himself has said in parliament.

We consider this sufficient clarification at worst, and a solemn promise at best, that the law will not be used by a minister against published speech that does not fall strictly under false statements of fact.

This is notwithstanding the legislative opinion by the authors of the UK's White Paper on Online Harms that disinformation has a less clear definition than a far longer list of harms which includes incitement of violence, sexting of indecent images, harassment, and hate crime. (see p.31). It is foreseeable that the very first legal challenge in the future to an application of this law will trigger when a minister decides to order a correction or removal of a statement that most early objectors to this bill have pointed out would be hard to demarcate as fact, opinion, satire, analysis, etc. The mere fact that this challenge is heard instead of summarily dismissed would indeed prove the superiority of the stand taken by the Rt Hons Savid Javid and Jeremy Wright, at which point the law ought to be sent back to parliament for required rectification and rethinking, or the law be acknowledged to have a far narrower application than currently imagined by both activists as well as the minister.

This is also notwithstanding NMP Prof Walter Theseira's speech in the debate where he unveiled his study of the Singapore government's Factually website. His conclusions after studying all the posts on Factually are damning. Prof Theseira claims the website exists mostly to dispute opinions and conclusions that run contrary to the government's narrative, and not false or wrong statements of fact. Whoever runs Factually on behalf of the government has the tendency to characterise fair but contrary conclusions and opinions as untruths. That the findings from his study were not denied or rebutted by the minister suggest that they are true.

Like Prof Theseira, we hope the cabinet will be more circumspect and intellectually honest when it comes to the application of this law. It is hoped that its seemingly cynical at best or incompetent at worst approach to distinguishing facts, opinions, and untruths in Factually is not an indicator and will not inform its application of this law.

We also thank the communications and information minister Iswaran for clarifying that his ministry is currently working with technology companies on the industry code of practice. We consider this sufficient clarification that the ongoing legislative process (which includes drafting the code of practice and getting the industry stakeholders to bind themselves to it) is for the most part, a consultative exercise and true dialogue between the executive, stakeholders and industry interests.

This clarification is essential in ameliorating the hard line and overcombative stance taken by junior minister Edwin Tong on the eve of the parliamentary debates, where he castigated an industry group voicing its concerns as only "a small group" "crying wolf" and conveniently left out any real world research proving his outlandish claims that most citizens want strong fake news laws. The junior minister may forget that campaigning for the bill's passage should have ended by the time the bill was first read in parliament. That "small group" was essentially the major stakeholders and industry interests voicing their concerns and misgivings. There is no conceivable reason to antagonise or demonise an entire industry that are participating in the consultation process and providing their honest feedback and concerns.

Where there has been a lack of clarifications

The major issue with the bill is how it turned from an instrument for protecting public order during the Select Committee process into an instrument for protecting public interest - which as defined by the bill, is a dubious and "not exhaustive" laundry list of things that do not look like public order issues at all, and cannot be reviewed by a judge during an appeal or review.

This bait and switch leaves a bitter taste in the mouth of moderates who lent their most reluctant support during the Select Committee stage to deal with hopefully rare, extreme threats by hostile state actors that posed clear danger to public order.

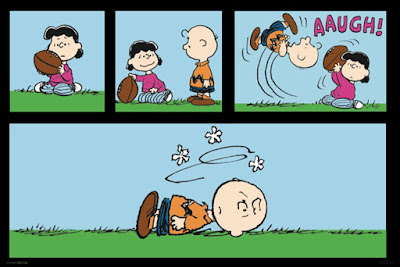

|

| The classic bait and switch, AAUGH! |

The parliamentary opposition appears to have missed this issue entirely and focused on getting the minister to define a threshold for which "public interest" is met. The minister understandably did not offer one, even though the Select Committee report makes reference to a "careful calibration to prevent public interest from being harmed" (para 50). To be fair to the minister, the threshold for "public interest" does not need to be explicitly defined; it is deduced from previous words and actions of this government, from every time the government brings up "public interest" to deny or offer information to the public.

From the government's recent actions, the public interest threshold is met when someone talks badly to the son of the prime minister and posts the video on social media, for example. It is met when the minister says he believes it would be better if the government has the power to use the law to "immediately clarify that this is false, and require the person and the online platform to push a notice to everybody" in the precise event that a rumour is spread about a roof of a HDB flat collapsing, even though no one actually took that rumour seriously, let alone created a panic about it. That is to say, the threshold of public interest never approaches the widespread panic, public order, riots, subversion of democracy or similar dire circumstances that the cabinet is more than happy to trot out when selling this bill to the public and in parliament. That is to say, there is a very low bar for 'public interest' that is at odds with how the bill has been rationalised and used to seek the previous consensus of the public. It is thus amazing how this bait and switch has not been challenged by the parliamentary opposition or by the NMPs.

Let us suppose the minister decides to make a correction or removal order on a statement that he argues is in the public interest but patently will not lead to riots, undermining of the democratic process, pose a threat to harmony, etc. A likely legal challenge could be that in the process of its passage, the law started off with public public order in its inception, public understanding, consensus, and then somehow changed to public interest in a bait and switch that had no explanation in the form of a white paper. No legislative intent has been stated for the change. The court in all likelihood will be unable to make a ruling and refer the law back to parliament for further clarifications, i.e. rewriting and more comprehensive debate on issues that have been ignored or denied in the recent debate. Will that happen? Why should Singapore wait for this humiliation to happen?

The option is still open for future ministers to exercise the new law only in strict public order situations, "public interest" clause notwithstanding. As with the much ballyhooed section 377A of the criminal code, it is possible for a contested law to be redeemed via far more judicious application by the executive.

No comments:

Post a Comment